Quantum computers promise speedy solutions to difficult problems, but building large-scale, general-purpose quantum devices are fraught with technical challenges. To date, many research groups have created small but functional quantum computers. By combining a handful of atoms, electrons, or superconducting junctions, researchers now regularly demonstrate quantum effects and run simple quantum algorithms — small programs dedicated to solving particular problems.

Making a quantum computer that can run arbitrary algorithms requires the right kind of physical system and a suite of programming tools. Atomic ions, confined by fields from nearby electrodes, are among the most promising platforms for meeting these needs. But these laboratory devices are often hard-wired to run one program or limited to fixed patterns of interactions between the quantum constituents.

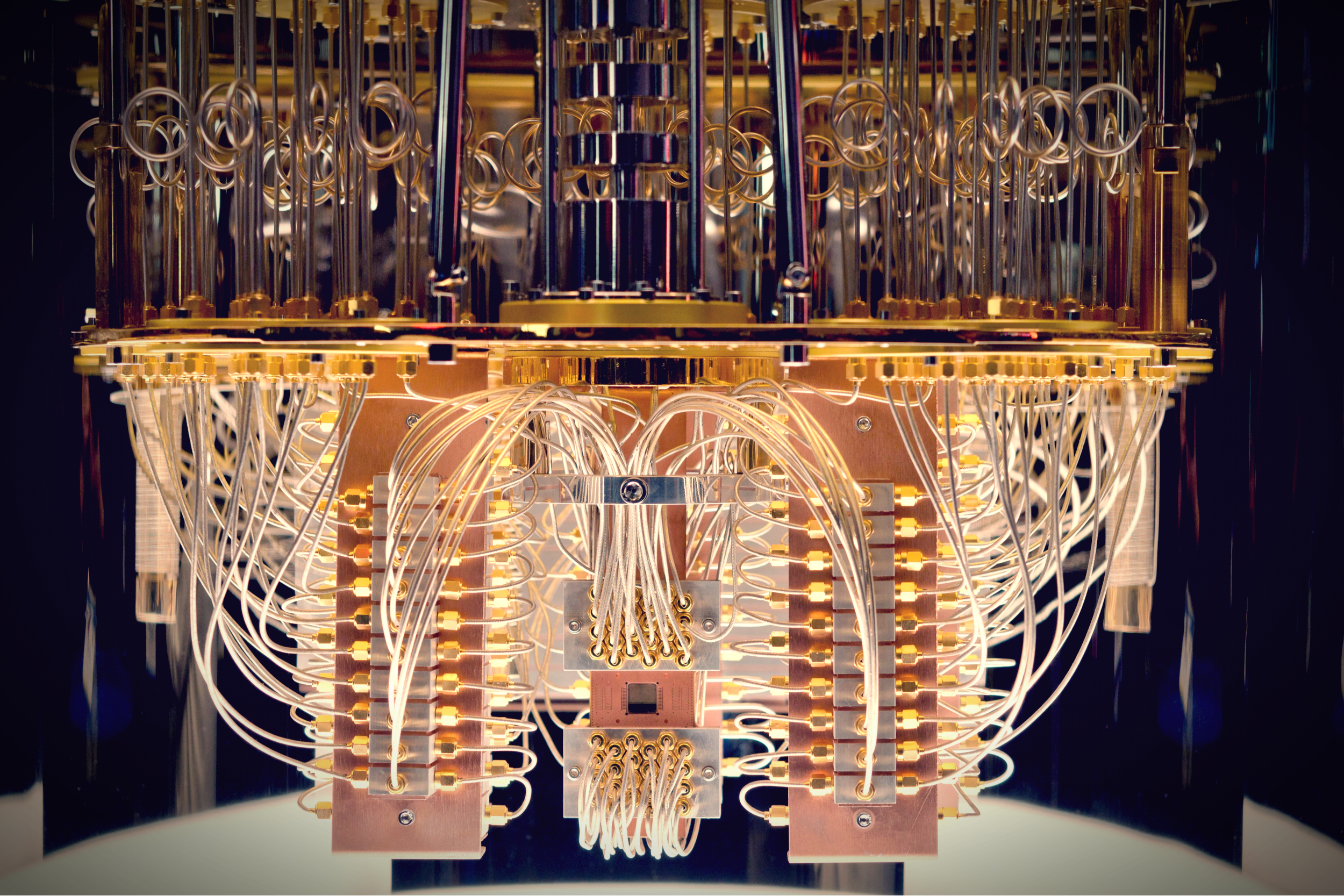

In a paper published as the cover story in Nature on August 4, researchers working with Christopher Monroe, a Fellow of the Joint Quantum Institute and the Joint Center for Quantum Information and Computer Science at the University of Maryland, introduced the first fully programmable and reconfigurable quantum computer module. The new device, dubbed a module because of its potential to connect with copies of itself, takes advantage of the unique properties offered by trapped ions to run any algorithm on five quantum bits or qubits — the fundamental unit of information in a quantum computer.

“For any computer to be useful, the user should not be required to know what’s inside,” Monroe says. “Very few people care what their iPhone is doing at the physical level. Our experiment brings high-quality quantum bits up to a higher level of functionality by allowing them to be programmed and reconfigured in software.” The new module builds on decades of research into trapping and controlling ions. It uses standard techniques but also introduces novel methods for control and measurement. This includes manipulating many ions at once using an array of tightly focused laser beams and dedicated detection channels that watch for the glow of each ion.

“These are the kinds of discoveries that the NSF Physics Frontiers Centers program is intended to enable,” says Jean Cottam Allen, a program director in the National Science Foundation’s physics division. “This work is at the frontier of quantum computing, and it’s helping to lay a foundation and bring practical quantum computing closer to being a reality.”

Related Articles :

- Alan Kurdi’s Death Has Changed Little for the World’s Refugees

- Somali Government Acquires Net Control Software for Social Media Security

- Samsung is rumored to have started work on an Android Oreo update for the Galaxy S8

- Do South American World Cup qualifiers put the Champions League to shame?

- Robots get creative to cut through the clutter.

The team tested their module on small instances of three problems that quantum computers are known to solve quickly. Having the flexibility to test the module on various issues is a major step forward, says Shantanu Debnath, a graduate student at JQI and the paper’s lead author. “By directly connecting any pair of qubits, we can reconfigure the system to implement any algorithm,” Debnath says. “While it’s just five qubits, we know how to apply the same technique to larger collections.”

At the module’s heart, though, is something that’s not even quantum: A database stores the best shapes for the laser pulses that drive quantum logic gates, the building blocks of quantum algorithms. Those shapes are calculated ahead of time using a regular computer, and the module uses software to translate an algorithm into the pulses in the database.

Putting the pieces together

Every quantum algorithm consists of three basic ingredients. First, the qubits are prepared in a particular state; second, they undergo a sequence of quantum logic gates; last, a quantum measurement extracts the algorithm’s output. The module performs these tasks using different colors of laser light. One color prepares the ions using optical pumping, in which each qubit is illuminated until it sits in the proper quantum energy state. The same laser helps read out the quantum state of each atomic ion at the end of the process. A separate laser strikes the ions in between to drive quantum logic gates.

These gates are like switches and transistors that power ordinary computers. Here, lasers push on the ions and couple their internal qubit information to their motion, allowing any two ions in the module to interact via their strong electrical repulsion. Two ions from across the chain notice each other through this electrical interaction, just as raising and releasing one ball in Newton’s cradle transfers energy to the other side.

The reconfigurability of the laser beams is a key advantage, Debnath says. “By reducing an algorithm into a series of laser pulses that push on the appropriate ions, we can reconfigure the wiring between these qubits from the outside,” he says. “It becomes a software problem, and no other quantum computing architecture has this flexibility.”

The team ran three different quantum algorithms to test the module, including a Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT) demonstration, which finds how often a given mathematical function repeats. It is a key piece in Shor’s quantum factoring algorithm, which would break some of the most widely-used security standards on the internet if run on a big enough quantum computer.

Two algorithms ran more than 90% of the time successfully, while the QFT topped at a 70% success rate. The team says that this is due to residual errors in the pulse-shaped gates and systematic errors that accumulate throughout the computation, neither of which appear fundamentally insurmountable. They note that the QFT algorithm requires all possible two-qubit gates and should be the most complicated quantum calculations.

The team believes that eventually, more qubits — perhaps as many as 100 — could be added to their quantum computer module. It is also possible to link separate modules together by physically moving the ions or using photons to carry information between them. Although the module has only five qubits, its flexibility allows for programming quantum algorithms that have never been run before, Debnath says. The researchers are now looking to run algorithms on a module with more qubits, including demonstrating quantum error correction routines as part of a project funded by the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity.